How a Russian Emigré I Never Met Changed My Life

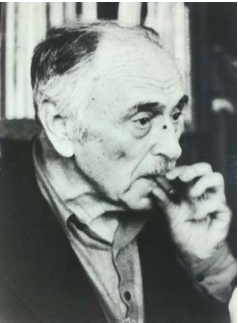

Norman Raeben

The following article was written by Laurie Weisman and published in the New York Art Teachers Association Winter 2019 Newsletter.

I met New York artist Roz Jacobs at a Valentine’s Day party in 1979, when she was 23 and I was 21 years old. I was completing an environmental science major and she was painting and waitressing. We hit it off, speaking about our lives in English, Spanish, French and Yiddish while hovering around the buffet table. I was struck by how much she spoke about her painting teacher, Norman Raeben, a Russian emigré, who had died a few months earlier. She’d dropped out of college to study with him and studied in a small class at his Carnegie Hall Studio every day for six years until he passed away at 78. In the first couple of years I knew Roz, not a day went by without a sentence that began “Norman said…”

She told me that while demonstrating in innumerable ways how light, movement and texture create shape in space, he simultaneously externalized his inner dialogue, unpacking the painting process while making connections to other artists or thinkers. He’d invoke people like Proust, Aristotle, Immanuel Kant and Isaac Newton as well as Matisse and Van Gogh and make connections between art, architecture and music. His emphasis was on “connectability” and an elasticity of thinking. He sounded like an amazing teacher.

Roz and I grew closer and I even took some painting lessons at that studio with Norman’s partner, Vicki. I learned how difficult it is to mix paint. My colors often came out murky brown and I soon got discouraged and gave up painting.

I also met Roz’s family. Both of her parents were Holocaust survivors. As I got to know them I was astonished by their joie de vie. How could these two individuals who’d experienced that horror be so warm and loving? I needed to understand their philosophy of life and how they coped with their memories. Roz and I decided we needed make a video record of their stories. We spent many hours over many years recording to their memories. We weren’t sure what we’d do with the material, but felt compelled to gather it.

In the meantime, Roz continued painting and exhibiting. I built a career in educational media, producing interdisciplinary media projects for companies like Children’s Television Workshop, Disney and Scholastic. Then, a series of events brought our careers together and transformed us both into art educators. It’s a surprising turn that neither of us could have predicted and it’s been a wonderful, life-changing experience. And it’s odd because Norman once said to Roz that she was going to do something important in a medium that hadn’t necessarily been created yet.

Here’s how it unfolded. A dear friend’s son died at 23, after many years of fighting cancer. She sent around a photo of him before he’d fallen ill. She asked people to write a story about Mischa for a memorial book. Rather than writing, Roz drew him. She created more than 20 pastels, unable to stop. The experience of painting him over and over again took her back to the days she was studying the head in Norman’s studio 30 years earlier. She remembered the lessons of her student days, the smell of Norman’s cigar smoke mingling with the smell of oil paint and turpentine. She remembered Norman’s lessons about analyzing the planes of the face. She felt a sense of the continuity of her own life. Gazing at Mischa’s image, she also saw the resemblance to members of his family and members of her own family who had passed away. She felt the connection to generations of family, to her younger self, and to her teacher. The feeling of loss was layered with deep and satisfying memories, arousing feelings more sweet than bitter. Creating art had given her tangible way to navigate the complexity of all of these feelings.

Original pastels of Mischa that inspired project

It also evoked thoughts in Roz about another young boy whose life had been cut short. Her mother had often spoken about a beloved younger brother named Kalman who had died in the Holocaust when he was about 14 years old. Her experience making pastels of Mischa inspired her to paint portraits of Uncle Kalman. We videotaped the painting process as Roz made nine different paintings of Kalman. There was a dual purpose. One was to bring viewers into the painting process. When people look at a work of art, they have no idea what went into it. Roz wanted to bring viewers into that process. The other goal was to find a creative way to share some of the stories we’d been videotaping for so many years. As can happen, when you start a project, it can become much more than you envisioned. Jacobs hadn’t anticipated the profound connection she’d feel with her uncle through the process of painting him over and over again. Looking deeply at his photograph for hours on end, she suddenly sensed the little boy standing in a photographer’s studio, looking up at the mysterious-looking box camera. It was almost an experience of time travel. She was able to replace the haunting thoughts of how he might have died with a sense of a child’s life force. It lifted a huge burden from her heart.

I used my skills in media production to help edit the videos and create the multimedia piece. It was exciting for me because I’d long wanted to collaborate with Roz on a project. We worked for more than a year on an Apple Powerbook to create the template for a nine-screen video installation. You can see the prototype on our website: memoryprojectproductions.com/exhibit.

The exhibit premiere was in a gallery in Florida, not far from where Roz’s parents lived. Her father was 85 years old at the time. He was a business man and had never responded to fine art. In fact, he had long worried about how his daughter would support herself as a painter. But he loved this installation and saw its power to reach people. After the opening, he said to her in his lilting Yiddish accent, “Teach the children, Rozzie.”

We took that to heart. Together, she and I developed a curriculum package that teaches a portrait-making technique based on an early lesson of Roz’s mentor, Norman Raeben. We created lesson plans and a curriculum guide. We’ve been doing classroom workshops and professional development. We formed a non-profit organization called The Memory Project Productions. The exhibit and program we created are used across the U.S., Poland and Hungary. We honor Holocaust victims, survivors and rescuers by making their portraits and sharing their stories. Then we make connections to students’ own stories so they discover that we are all part of history and all of our stories matter. At first we worked with history teachers, but quickly realized that they wouldn’t be likely to take continue the project on their own. However, art teachers see the potential and appreciate the project’s multidisciplinary aspects. Working with art teachers is addictive. Their passion and commitment to making a difference is profound.

So through the remarkable chain of events, Norman Raeben, a Russian-born painter, who died in 1978, inspired Roz, then me, and now thousands of people around the world. His teaching brought other great thinkers and artist into the room. So, in a way, he opened the door so that the whole world could become your mentor. His legacy is helping us to use “connectability” to make links between art, history, memory, and language arts. It’s helping create communication across generations and cultural divides as students learn and share historical stories as well as their own. We display the thousands of portraits that kids around the world have made on an interactive website—fulfilling Norman’s prescient vision that Roz would work in some new medium. And we honor her parents’ legacy of love by telling their stories and cultivating creativity and compassion so that their dream of “Never again” can become a reality.